Sanghita Singh speaks to Nicholas Vreeland, abbot of the Rato Dratsang monastery in Karnakata discovering his unique journey and simple wisdom that we can apply to our daily lives.

In our daily material pursuits and living, what do we miss that a monk may find by giving it all up? The obvious answer would be peace, calmness, and tranquility of mind, but what if you meet a monk who confesses that he experiences mental travails similar to a lay person? That he feels anger, irritation and disappointment when things don’t go his way. That the robes are not necessarily his armour against negative human emotions?

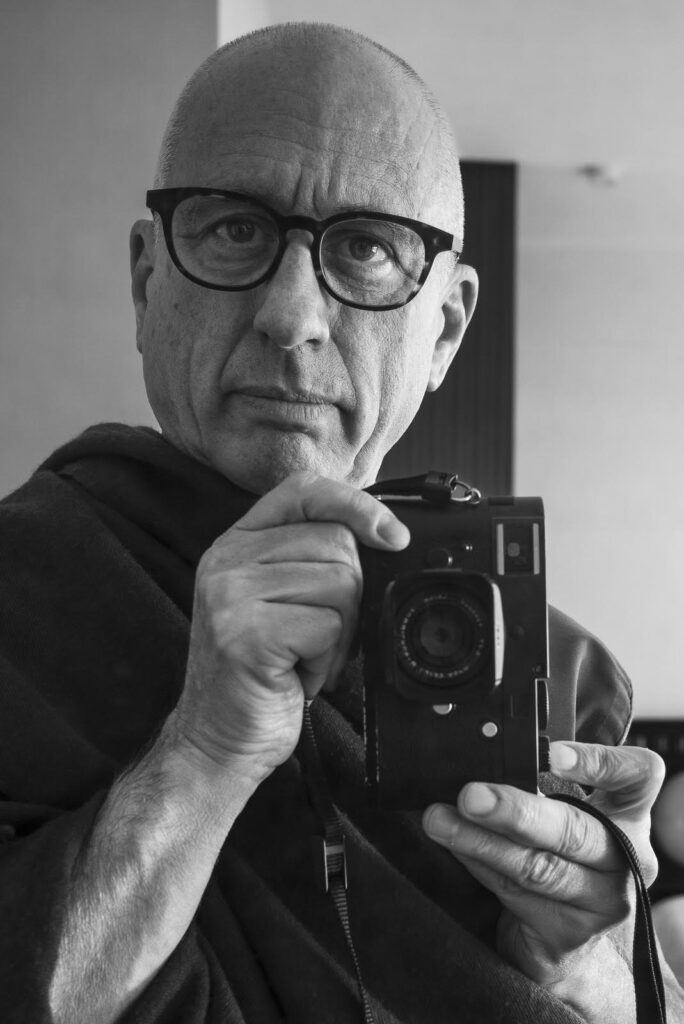

Nicholas Vreeland, a photographer and monk, debunks the popular perception of monastic life. “I don’t want to pretend that I am not confronted with such challenges and that I necessarily deal with them well. A monk has as many challenges and struggles as anyone else. I get frustrated with my own sloppiness, my own laziness, as well as the sloppiness and laziness of others. And sometimes, that makes me angry,” he shares.

He explains that the difference, however, is that a monk chooses to work on himself in diminishing his self-cherishing tendencies. “When I say a monk, a nun has chosen to work on herself. And you don’t have to become a monk or a nun to take that decision, but let’s say that becoming a monastic makes the process easier. The monastic rules, the monastic community all protect one and help along this path of working one oneself,” offers Vreeland.

The ‘work’ involves living by a set of rules so one is more aware of one’s challenges and develops the ability to deal with them. His day begins with setting a motivation. “It helps develop the muscle of mindfulness, the muscle of self-discipline. It helps me refrain from jumping at a situation. The more we do this, the more we develop that ability. The more we strengthen that muscle, the more we can refrain from outbursts (of anger). I think it will take lifetimes before I can actually remain calm in many such situations, but that’s the work,” says Vreeland who has spent a large portion of the last two years with his teacher, the 98-year-old Khyongla Rato Rinpoche, in Dharamsala.

The pandemic, for most of us, has been a revelation at many levels, and this is true even for someone like Vreeland who has cloistered himself in his monastery for decades before we were forced into lockdown and isolation. “I’ve come to see the beauty of Himachal Pradesh as I’ve never seen it before—I came here first 43 years ago, but I never noticed how magnificent the place is. I think if one can see the world around one being magnificent, that somehow uplifts us in a wonderful way—the work that we do on ourselves spiritually doesn’t take us to some other place. It simply changes the way we perceive the world around us. And I think this time has given us the opportunity. It forced us to slow down. We can either resent the situation or we can let go and simply appreciate each moment, appreciate each situation and the environment we can find ourselves in,” he explains.

As we talk to each other on Zoom, embracing the new normal of the way people meet, I try and look for any traces of his former life, but I find none. It is difficult to see him as the grandson of the former editor of Vogue, Diana Vreeland, or the son of an American diplomat who travelled the world, partied and dated women before embracing monkhood. His maroon robes and black-rimmed spectacles sit easily on his personality. The transition from a man of fashion to a man of faith is interesting, but what is more interesting is that the experience has not left him with any distaste for his past life. Did he, at any point, think that he was done with the world?

“I am not sure if I think that the attitude of ‘I am done with the world’ is a real one… if it is an honest one. I think a spiritual pursuit should be a positive one, not putting the past behind one. It is transforming the present into a future imbued with spiritual values. And what are our spiritual values? The spiritual point of view, or a spiritual aim, I profoundly believe in is one in which we work on ourselves towards making our commitment to helping others, more important than our commitment to satisfying ourselves. That doesn’t have to be done within a religious or a formal context of any sort. That’s something that one works at doing inside in one’s self. It’s an inner evolution which demands work but I s inner work,” he explains.

The lesson Vreeland offers is that the spiritual life is not about chasing rainbows—far from that! Rather, this is a reminder that our struggles will remain as long as we are alive. “I am just working on myself, and there are times when I struggle, times when I have to push myself to maintain my self-discipline, times when the process seems to be a little bit easier,” he says, giving us hope that if we are willing to do the work, some days will reward us with being easy.

Photos from the Rato Dratsang Monastery by Nicholas Vreeland

PRACTICAL LESSONS TO FOLLOW IN EVERYDAY LIFE

How do you start your day?

You know what determines the quality of one’s day is the way in which one sets forth on that day. I begin my day by getting out of bed, putting on my dressing gown, making three prostrations to the Buddha and my teacher and determining that I will work at diminishing my self-centred, selfish attitudes and devote myself to the pursuit of enlightenment by which I can best serve others. That is how I start my day.

What is your ritual before going to bed?

Again, I make my three prostrations—the thought that one is meant to give before going to bed is to look over the day, look over our actions and see the situations in which we have not done so well. The situations in which, let’s say, we have become angry, frustrated, been a little sloppy or lazy or whatever it is, and develop regret for having behaved that way and develop a determination to work on oneself to do better the next time. We should also look over the good things we’ve done and develop a certain joy, a delight in the fact that we were able to, let’s say, act generously, that we refrained from getting angry. That rejoicing in our accomplishment helps in our ability to behave that way in the future.

How does one deal with the sadness and anxiety of living in uncertain times?

When the situation is such that we recognize that we really can’t do much about it, that’s what makes us determined to work on ourselves so that we ultimately can help others. That’s the bodhisattva attitude. The concept of bodhichitta, the mind of enlightenment, and the determination to be able to work towards serving others helps the bodhisattva to assumes that determination. And you develop that determination as a result of being confronted with overwhelming suffering. This situation is tragic as it is, provides all of us an opportunity to say “I am not equipped. I must work on myself so that I really can help others.”

Can you recommend a meditation practice to get over anxiety, fear and lack of confidence?

The first thing we have to do is develop calm, a certain steadiness, and we do that by simply following our breath—in and out! We simply watch the breath going in and out. When we bring our mind and our breath together, that is, in itself, calm. Once we have achieved this, we have to think about the suffering of others. We must wish to remove it. We must think about the joys that we have and have the wish to provide that to others. We can’t remove the suffering of others but if we can develop that wish and if we can think about that wish that we will remove the suffering of others –that becomes a wonderful simple living meditation.

Nicholas Vreeland’s interview is available on The Positive Podcast

Nicholas Vreeland is the abbot of Rato Dratsang, an important Tibetan government monastery under the patronage of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. A New York Times best-selling author and photographer, Vreeland is also Director of the Tibet Center, the oldest Tibetan Buddhist Center in New York City. He is a Buddhist monk and holds a Geshe degree, the equivalent of a PhD. Born in Geneva, Switzerland, to American parents, Vreeland was educated in Europe, North Africa and the United States, after which he pursued a career in photography. In the late 60s and early 70s, Vreeland worked as an assistant to Irving Penn and Richard Avedon and studied film at New York University. In 1977, he met his teacher Khyongla Rato Rinpoche, the founder of the Tibet Centre, and became a monk in 1985.

A motivating discussion is definitely worth comment. Theres no doubt that that you should write more on this issue, it may not be a taboo subject but usually folks dont talk about these subjects. To the next! Kind regards!!